At Michaela, we receive hundreds of visitors each year. As Head of Art, I find that the most common questions visitors ask me fall into two camps: first, people often ask something along the lines of “when are the pupils allowed to be creative?” Secondly, (and often after seeing examples of our pupils’ artwork), they ask “how do you get them to produce work of such a high standard?!”

The answer is simple: I tell them how to do it, they practise, and eventually, they get better at it. It isn’t any more complicated than that.

The Michaela ‘just tell them!’ philosophy enables our pupils to reach a high standard in Art. Whilst in the past I have seen pupils lacking in natural artistic flair fall behind and flounder in Art lessons, giving the subject up as soon as they can, Michaela pupils are able to master the fundamentals of drawing and painting, and learn to appreciate art and its cultural significance. It’s not without difficulty, of course- and indeed, many pupils do struggle in art just as they can struggle in any subject, but a key distinction between the Michaela approach and that of many art departments I know is that we believe that drill and practice are the foundations of creativity, and more importantly, we believe that every child can do it if they are taught explicitly. Rather than promoting creativity for creativity’s sake, or allowing kids to splash about with paint with little real focus, we spend time explicitly teaching and securing the basics.

What are the basics?

Here is what we have identified as the building blocks of Art. These are the fundamental basics that underpin and strengthen creativity.

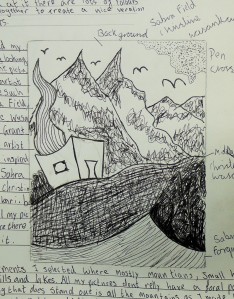

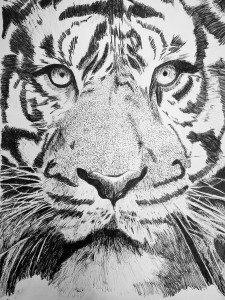

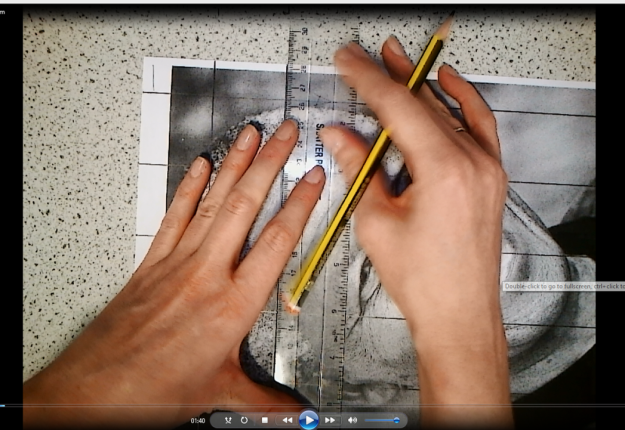

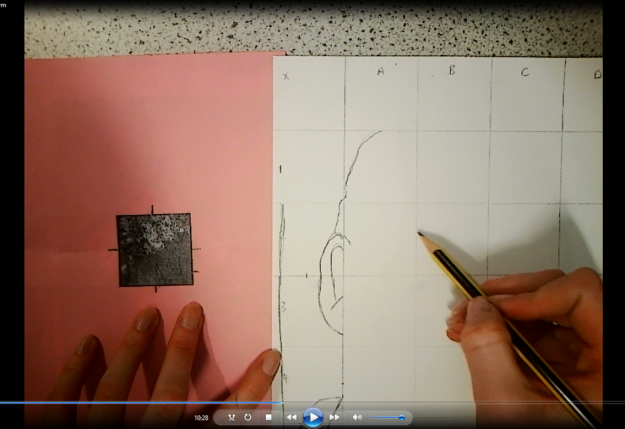

- Media: We teach pupils explicitly in the use of pencil, charcoal, chalk, pen, paint, oil pastel and printing. We show them exactly how to hold the media, when and how to apply pressure, and how to achieve various effects.

- Shape: Pupils learn exactly how to draw different shapes. I model this on the visualiser and pupils copy before recreating their own shapes.

- Shading: At the very beginning of year 7, pupils learn how to shade using pencil. They are drilled in the ‘tonal ladder’, regularly practising shading to varying degrees.

- Colour: Pupils need to understand how colours relate to each other and how they are created from the primary colours up. We spend time securing this knowledge at the start of year 7.

How to embed the basics

- Revisiting: Pupils constantly re-visit each media, every half term, every year, so skills and techniques are practised over and over again.

- Interleaving: Media and techniques are carefully sequenced and interleaved to ensure pupils are able to use them both in a variety of contexts. Basic skills such as shading are used continually throughout the majority of units to secure them.

- Speed: We don’t rush through units. Mastery takes time. It’s better to spend a long time embedding the fundamentals before racing on to more complex skills. As we say at Michaela, “don’t nearly know it- really know it!”

- Mindset: I don’t want any pupil to ever tell me that they are not good at Art, or that they aren’t a particularly artistic person. Whilst it is the case that some are more naturally attuned to the artistic world than others, all pupils can learn how to draw and paint if they are taught. We do not believe that asking pupils who struggle to ‘have a go’ or ‘experiment and be free’ is a good strategy. Instead, we plan for purposeful, motivating art lessons that build incrementally on each other until pupils have internalised the fundamentals. From there, pupils are able to develop their skills and produce fantastic pieces of work.

Mindset and practice: these are the cornerstones of the entire Michaela philosophy. We believe that the best route to unleashing creativity in our pupils, and enabling them to become successful artists, is to drill them in the basic components of drawing and painting.

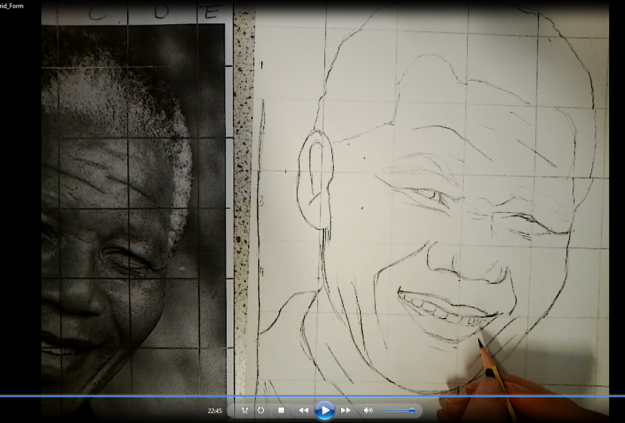

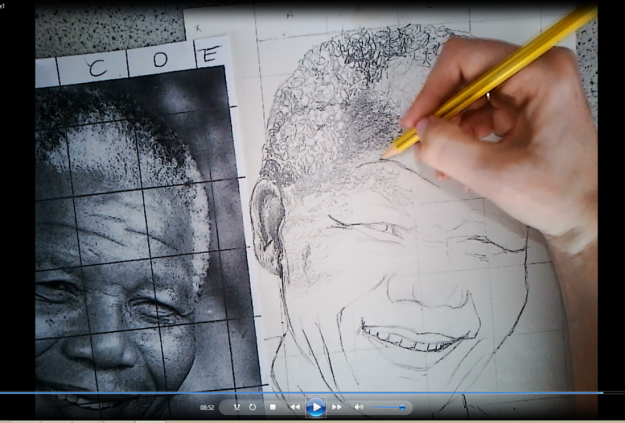

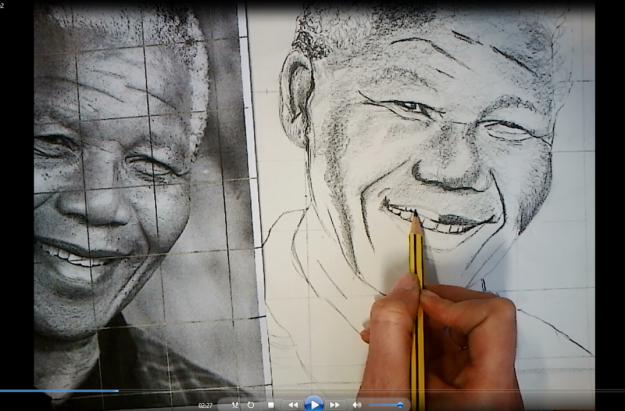

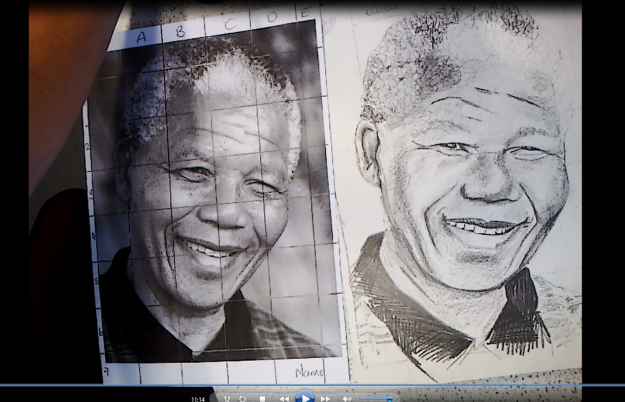

Below are some examples of our pupils’ work across years 7, 8 and 9.